One out of every four children attending school has been exposed to a traumatic event that can affect learning and/or behavior. ACEs have a major impact on how a child behaves, learns and understands in a school setting.1

Some facts:

- ACEs can impact school performance.

- ACEs can impair learning.

- Children who have experienced ACEs may feel physical and emotional distress in a school environment.

When children experience mental distress as a result of exposure to ACEs, areas of the brain that are responsible for emotional and affect regulation are negatively impacted. Children often normalize around the ACE(s) they have experienced, and this normalization of the stress response causes brain cells to slow and suppress the ability to build self-regulation skills.2

ACEs can cause toxic stress, which prevents the development of neuropathways that enable a child to access the self-regulation skills that are developed in the frontal cortex of the brain. This can impair awareness, emotional intelligence, emotional attunement, social cognition, and interpersonal competence.3

While the effects of ACEs on school-age children can be devastating, it does not have to be that way. We can identify, engage, and take action to help produce better outcomes for children in the classroom.

Identifying ACEs in the school setting.

Common indicators of toxic stress include responding to typical stimuli with hypervigilance and hyperarousal, fear, and dissociation.

Signs a child may have experienced ACEs by grade level:

This is not a comprehensive list of signs; as there are many more that manifest themselves differently depending on the age and child. These are merely examples and may appear in a student at any grade level.

Elementary School

- Anxiety, fear, and worry about safety of self and others (more clingy with teacher or parent).

- Increased distress (unusually whiny, irritable, moody).

- Changes in behavior, such as decreased attention or concentration, withdrawal from other students and activities, or angry outbursts or aggression.

Middle School

- Worry about recurrence or consequences of violence.

- Changes in behavior (increase in activity level or decreased attention and/or concentration).

- Increased somatic complaints (e.g., headaches, stomachaches, chest pains).

High School

- Negative impact on issues of trust and perceptions of others.

- Heightened difficulty with authority, redirection, or criticism.

- Increase in impulsivity, risk-taking behavior.4

In the past, teachers may have observed these children as hyperactive, aggressive, depressed, and restless. Often, those children were referred to clinics and diagnosed with ADHD, anxiety, and/or mood disorders that do not target the root of the trauma.5 We need to be proactive in the school setting at establishing guidelines for dealing with ACEs. We need to engage in conversation about ACEs to understand their impact on children.

You’ve identified that a child may have experienced ACEs. Now what?

Have the conversation

Establish a school-wide understanding that teaching and responding to students who experience the effects of ACEs will ultimately help promote academic and social emotional growth.6

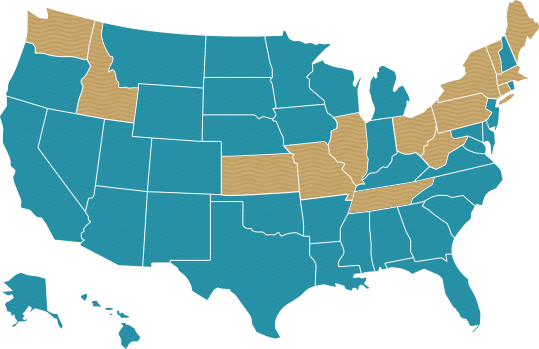

In fact: 17 States have already adopted Social Emotional Learning Standards for school-age students. Ohio has adopted statewide standards for grades K-3.7

| States with preschool standards | |

| States with preschool and K-12 standards | |

Discuss your policies

Discuss your policies around discipline, detention, and in-school and out-of-school suspensions and expulsions. Do you have higher rates than average? Think about the child experiencing toxic stress and their behavior – how will suspension or expulsion from perhaps their only safe environment impact them?

Build your classroom for comfort

Regardless of any ongoing crisis or disability a child may suffer from, students need support to be successful in school. Below is a list of things you can do to better design your classroom for comfort. It is not a complete list, but it can be a good place to start.

- Modify or shorten assignments and offer individual tutoring or support.

- Give extended time for a student to complete an assignment or task and assist the child with organizing and remembering assignments.

- Allow the child to leave class to go see a school-based mental health professional, if the child is struggling emotionally. Try to engage caregivers in providing academic support at home.

- With the child, explore if there is something that provides comfort such as a memento or item from a loved one that can be brought to school.

- Help the child identify effective soothing techniques such as drawing, deep breathing, or exercising that can be utilized in school to manage emotions.8

Take action to build resilience.

Since children spend a great deal of their young lives in a school setting, our role to develop resilience in them is critical.

The presence of resilience factors can decrease or eliminate the impact that ACEs can have on children. These factors include:

- Being a positive and protective caregiver and building a sense of support.

- Providing professional support for the child/family if needed.

- Finding peer support and positive social relationships.

- Nurturing effective coping skills and problem-solving skills.

- Boosting high self-esteem and self-confidence.9

We’re in this together.

Local and national resources are eager to help you and your organization become better prepared to help children who are experiencing ACEs and toxic stress.

- Connect with Joining Forces for Children to learn about other local organizations and resources.

- Or nationally, join ACEs Connection: a community-of-practice social network (http://www.acesconnection.com/).

Need a question answered?

Or for additional resources:

- The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. “Child Trauma Toolkit for Educators.” October, 2008.

- Guenette, F., Kitchenham, A., & O’Neil, L. (2010). Am I safe here and do you like me? Understanding complex trauma and attachment disruption in the classroom. British Journal of Special Education, 37 (4), 190-197.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. “Helping Foster and Adoptive Families Cope with Trauma: A Guide for Pediatricians.” Healthy Foster Care America. 2017. Retrieved from https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/healthy-foster-care-america/Pages/Trauma-Guide.aspx#trauma

- The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. “Child Trauma Toolkit for Educators.” October, 2008.

- Guenette, F., Kitchenham, A., & O’Neil, L. (2010). Am I safe here and do you like me? Understanding complex trauma and attachment disruption in the classroom. British Journal of Special Education, 37 (4), 190-197.

- Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning. January, 2017.

- Ohio’s New Learning Standards, K-3, Social Emotional Learning. http://education.ohio.gov/getattachment/Topics/Early-Learning/Early-Learning-Content-Standards/Ohio%E2%80%99s-Kindergarten-Through-Grade-3-Learning-and-D/K-3-Standards.pdf.aspx

- 9. National Association of School Psychologists. “Supporting Students Experiencing Childhood Trauma: Tips for Parents and Educators.” http://www.nasponline.org/resources-and-publications/resources/school-safety-and-crisis/trauma/supporting-students-experiencing-childhood-trauma-tips-for-parents-and-educators